|

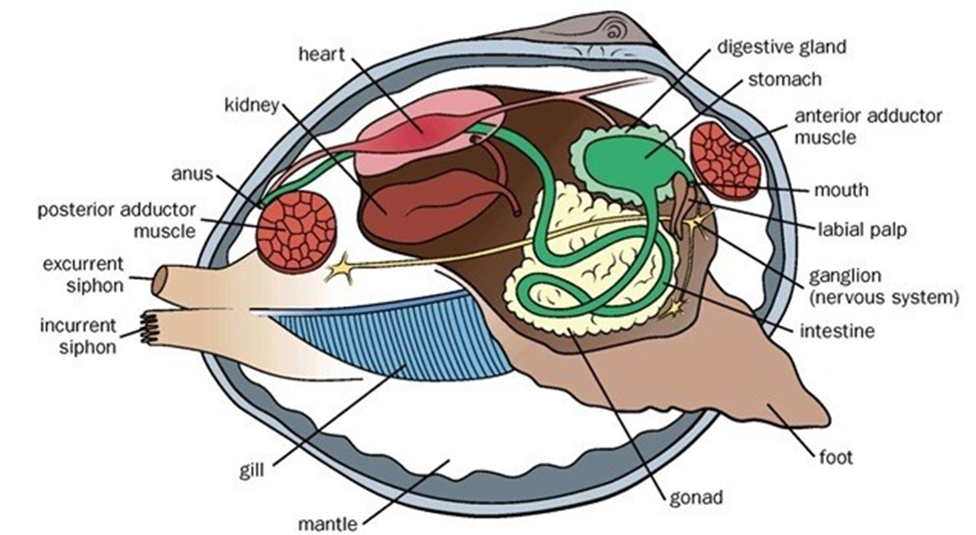

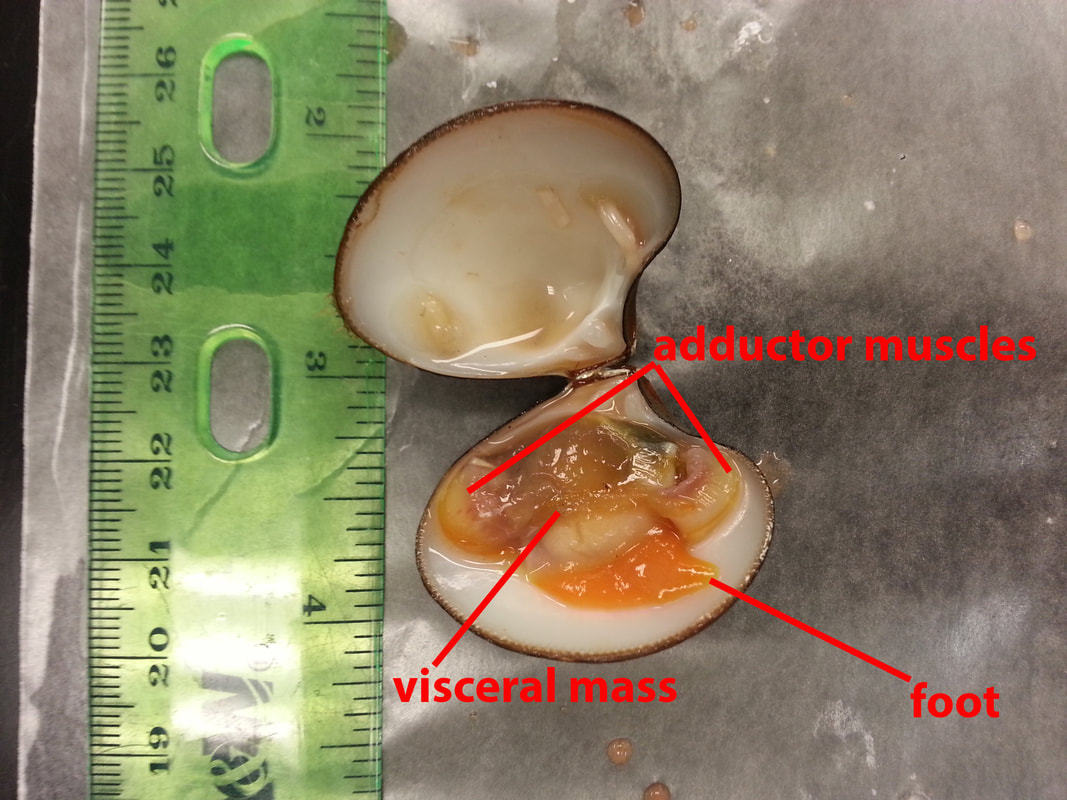

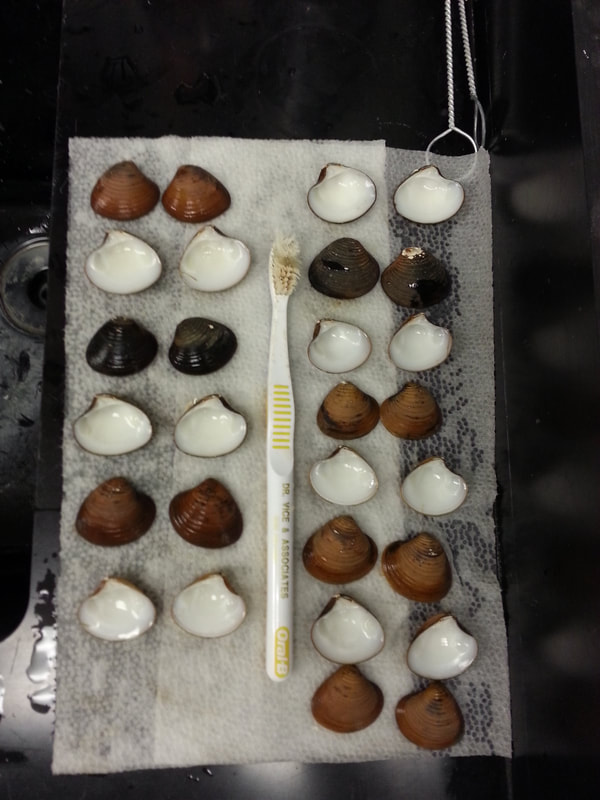

Ooooh that smell Can't you smell that smell Ooooh that smell The smell of death surrounds you” – Lynyrd Skynyrd, That smell Wet dog. The bottom of a dumpster on a summer day. A decomposing fish. Old socks. A touch of salt water. What smells like a combination of all those? Two year old, once frozen but now partially defrosted clams. It is probably not what Lynyrd Skynrd was referring to but the smell of death filled the Paleo lab at UNC last week. A few days ago I received a shipment of clams from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS, www.vims.edu) via FedEx (you can ship almost anything in the mail). Among many other things, VIMS conducts surveys of marine creatures living on the seafloor. A few times a year a research vessel goes out and dredges the sea bottom at various areas along the Atlantic Coast. The data collected from these cruises are used to inform the public, industry, and policy makers about the status of many economically important marine animals. Researchers like myself use these samples for scientific studies. My work at UNC examines the consequences of environmental change on the bivalve Astarte and I was fortunate enough to receive 100+ individuals from a series of dredges from Massachusetts to southern Virginia. A look inside the styrofoam container the in which the clams were shipped. Note the camouflage lunch box. The number of everyday items scientists use always amuses me. I think most people assume we are using fancy, expensive equipment but most of the time it is stuff that can be purchased at your local Wal-Mart. So what do you do with a bunch of stinky, old clams? Science! Step one, scoop out the goop. Not the technical term, but for my work I am interested in growth increments preserved in the shell so thankfully the squishy stuff (which is the smelly part) can be discarded. Most of it is easily scrapped out using a scalpel but for the sticky bits, a soft toothbrush does the trick. I’ll admit, before I started working with clams I kind of thought they were rather simplistic and boring animals. However, this is not the case. Clams, like us, have a rather complex organ system. In the diagram of clam anatomy below you’ll notice that we share many of the same organs as clams (e.g., heart, kidney, stomach, anus [yes, everything poops]), but also that there are a few differences (e.g., gills, siphon). Though they have an organ called a foot, clams cannot walk. However, the foot, which is a muscular like organ, does help them burrow into the sediment and sometimes avoid predators (watch this cool video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_KVFDfv6R2M). A diagram of internal clam anatomy. Taken from here http://what-when-how.com/animal-life/class-bivalvia//, but I doubt that is the original source. What I refer to as the “goop” is actually the organs of the clam, which are contained in the visceral mass. The adductor muscles actively close the shell. The foot helps the clam burrow into the seafloor. It is hard to see all of the organs if the clam is not prepped for dissection. Both values of several individuals after the goop has been cleaned out. Note this toothbrush is used for lab purposes only. Step two. What have we got? First a sidetrack. My master’s thesis at the University of Oklahoma dealt with phylogenetic (evolutionary) relationships of a group of trilobites (Moss and Westrop 2014). Determining phylogenetic relationships requires detailed taxonomic study so I spent an inordinate amount of time staring at and taking pictures of trilobites, and trying to reconcile minute differences to identify the species I was working with. One day, my advisor said to me “all you need to know for this project, you learned in kindergarten.” Of course, that is an oversimplification, but in some ways, he was right. At its most basic level, my project was one of those spot the differences activities they give children to keep them entertained at IHOP. Except I was not using crayons. Google image search trilobites real quick if you are not familiar with them and you will see that they are an incredibly diverse group with lots of different shapes and features. If you are doing taxonomic work on trilobites, you have a lot to work with. Now google image search clams. One of my Ph.D. committee members, Jim Brower, liked to refer to clams as amoeboid shaped objects. Honestly, it is not a bad description. After not doing any real taxonomic in my PhD work, I thought I was done with it. Life lesson, you never know when or how skills you have acquired will come in handy. Taxonomy, the science of naming organisms, is an old discipline. Carl Linnaeus is the so-called “father of taxonomy” and the birth of taxonomy is usually credited to his Systema Naturae in 1735. With this publication, Linnaeus became one of the first scientists to consistently use a hierarchical system of classification in naming organisms. Most high school biology students are required to memorize Linnaeus’ classification, but I think most people forget shortly after. Kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus species. Linnaean taxonomy also gives a binomial nomenclature for naming organisms in which every organism is identified by a genus and species name. When written, these are always either italicized or underlined and the genus is always capitalized. When first encountered in a scientific publication an author is typically included in parentheses with the year it was first described. For example Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Linnaeus, 1766) is scientific name for the bald eagle. One more time just for fun. Kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species. The genus Astarte was first named in the 1800s (Schumacher 1817) and now contains over 30 accepted species (www.marinespecies.org). Its’ taxonomy is rather complicated and there are many differing scientific opinions on species differences. The first few sentences of most papers I read included the world difficult. In the world of taxonomy, there are splitters and there are lumpers. Splitters like to create many species based on small variations, whereas lumpers tend to create fewer. Most Astarte workers appear to have been splitters as some of the differences between species are incredibly minute. Complicating the matter further, there can be a good deal of shape variation within a single population! I was hoping to get A. borealis from the VIMS cruises to compare to another study from the White Sea (Moss et al in prep). After losing much sleep, (though admittedly part of that was due to having an 11-month-old son) I determined that I got not only A. borealis, but also A. subaequilatera, and A. castena. This is exciting because it will allow me to establish a latitudinal gradient from NC to NY in lifespan and growth rate of three modern species of Astarte. I can then turn to a time in the fossil record when temperatures were much warmer and potentially understand what might happen to these (and other) clams as Earth continues to warm. But first, I need to cut, polish, image, and conduct isotopic analyses on these shells (for another post). From left to right: Astarte subaequilatera, Astarte castena, and Astarte borealis. The smell of science, however unpleasant, is only temporary. The goop has been properly disposed of and counters cleaned and disinfected. For a day, the paleo lab was lemon fresh. Now it is back to nitrile gloves and burnt plastic. Ooooh that smell. References

Moss DK, Surge D, Khaitov V, Lifespan and growth of Astarte borealis (Bivalvia) from Kandalaksha Gulf, White Sea, Russia. To be submitted to Polar Biology (October, 2017). Moss DK, Westrop SR (2014) Systematics of some Late Ordovician encrinurine trilobites from Laurentian North America. J Paleontol 88:1095–1119. doi: 10.1666/13-159 Schumacher C (1817) Essai d’un nouveau systeme des habitations des vers testaces. Copenhagen

0 Comments

|

AuthorDavid Moss. Paleontologist. While most of my blog posts will relate to my research, from time to time I plan to write about something completely unrelated. I like to tell stories to communicate scientific ideas. Hopefully they will be entertaining as well as informative.

Archives

November 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed